The Power Law reminds us to think bigger. People systematically misperceive long tail risk, which creates arbitrage opportunities for those who manage uncertainty well. We discuss five strategies to identify and exploit long tail opportunities.

Would you make an investment that promises a 10% chance of making a 100x return?

In Amazon’s 2016 shareholder letter, Jeff Bezos says you should take that bet every time. He took that no regret decision leaving a job on Wall Street to start Amazon. His net worth now exceeds $200 billion. Ambitious startup founders and early-stage venture investors routinely make these bets when they launch or invest in startups.

This thinking diverges from traditional investment strategies that focus on minimizing risk and securing steady returns. Rarely do such wagers present themselves and, if they were readily visible, then pricing adjusts to neutralize arbitrage opportunities. Other factors complicate real world decisions. Is a 100x return realizable? What are the consequences in the 90% loss scenario? What if losses involve reputational loss, forfeiting one’s career, bankruptcy or loss of life? The saying “there is no free lunch” applies to most situations, so caveat emptor – buyer beware – is often prudent when presented with such ‘opportunities’.

Yet life would be bland, bereft and barren if we summarily ignore lucrative opportunities. Venture investors initially dismissed Amazon, which took a year to raise its first round of financing. The investors who passed forwent a deal far better than Bezos offered in the 2016 annual report: a $50,000 early investment in Amazon would be worth $27 billion in 2026.

Investors and entrepreneurs need to think bigger as they often fail to fathom the upside potential of disruptive ideas. Few appreciate unconventional, disruptive ideas at the outset as they often emerge inchoate and are refined until they find product market fit. The list of future unicorns that were initially ignored is long. Among recent tech unicorns IPOs, nearly half had difficulty raising initial funding. The list includes iconic tech firms such as AirBnB, Datadog, Peloton, Pinterest, Robinhood, SquareSpace, Toast, Uber and UIpath.

Peter Thiel was so frustrated with the conformist thinking of venture investors when pitching PayPal, now worth over $50 billion, that he started Founders Fund to invest in unconventional, high potential founders. Founders Fund has performed spectacularly well, yet it too passed on Uber and others in the above list.

Fortunately, founders need only one yes from investors to launch their business. Still, one wonders how many how many founders were meant to scale the heights but, faint of heart, turned back when almost there. The Bessemer anti-portfolio honors only future successes that Bessemer Venture Partners missed. How much longer is the list of game changing ideas that never came to fruition when budding entrepreneurs took no for an answer or, worse yet, they were summarily rejected by all?

The Power Law: How it Applies to Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital

The Power Law offers the prospect of outsized outcomes for outliers.

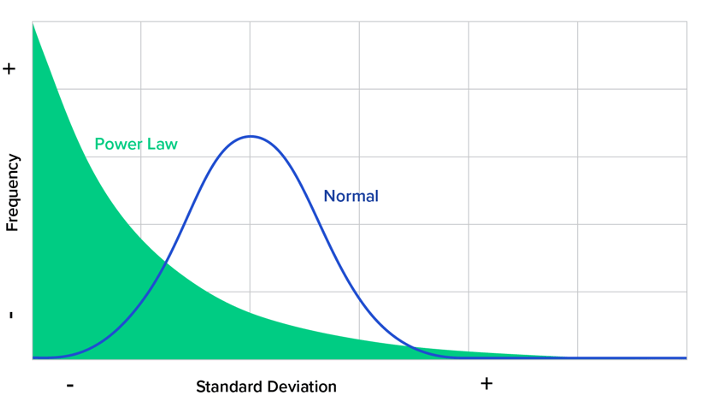

Power Law outcomes are unevenly distributed as a few winners dominate while most entrants remain small or fail. The Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 rule, applies when 20% of the population produces 80% of the results. The Pareto Principle and Power Law refer more broadly to skewed results, so the disproportionate ratio could be 90/10 or 95/5. The Power Law differs from normal distributions in which two-thirds of results are within one standard deviation of the mean and 95% are within two standard deviations. Figure 1 illustrates the difference between Power Law and normal distributions.

Figure 1: Power Law v. Normal Distributions

Entrepreneurship and venture capital are subject to the Power Law. As Benchmark partner Bill Gurley observed, “Venture capital is not even a home run business. It’s a grand slam business.” Bezos elaborated: “The difference between baseball and business is that baseball has a truncated outcome distribution. When you swing, no matter how well you connect with the ball, the most runs you can get is four. In business, when you step up to the plate, you can occasionally score 1,000 runs.”

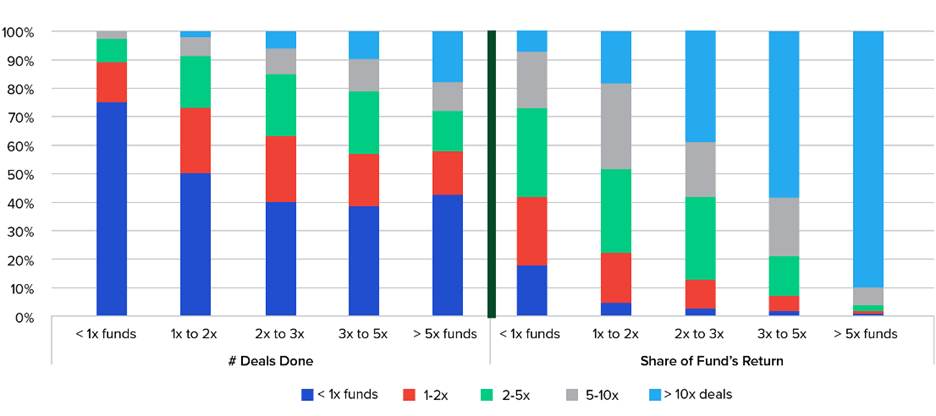

An analysis of venture funds in which Horsley Bridge has invested illustrates this point in Figure 2. The loss rate remains between 40-50% for funds that returned 1-5x+ (see dark blue in # Deals Done) while fund returns on deals that returned more than 10x capital invested increased from 20% for 1-2x funds to 90% for 5x+ funds (see light blue in Share of Fund’s Return). The Power Law for the best performing 5x+ funds is over 90/20. Since Horsley Bridge invests in established, proven funds, the results presented in Figure 2 understand the impact of the Power Law in venture. Actual early-stage loss rates are reportedly about 75%, so the Power Law for early-stage venture is on the order of 90/10 or more.

Figure 2: Deal Distribution – Number of Deals and Share of Fund Returns

Source: Horsley Bridge

The Power Law applies widely in Winner Take Most markets, which includes any industry subject to network effects or economies of scale. Following are just a few areas in which the Power Law applies:

- Financial concentration: The Magnificent Seven – Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla – now accounts for 32% of total U.S. market value among 8800 publicly listed stocks. The top five banks have a 54% market share among the 100 largest U.S. banks.

- Industry concentration: The top three U.S. firms account for 95% of computer manufacturing, 87% of social networking sites, 87% of online grocery retail, 85% of aerospace and 83% of big box retailers.

- Geographic concentration: 75% of Americans live in cities covering just 2% of the land, 58% of U.S. patents come from ten U.S. cities, and five metros account for 90% of new tech jobs.

- Wealth concentration: The top 1% holds over 30% of U.S. assets while the bottom 50% holds 2.5%.

The U.S. has long been a magnet for talent as it rewards rugged individualism. A land of The Haves and Have Yachts, America also pays to be in the right place at the right time.

The Power Law: Challenges Assessing Abnormal Distributions

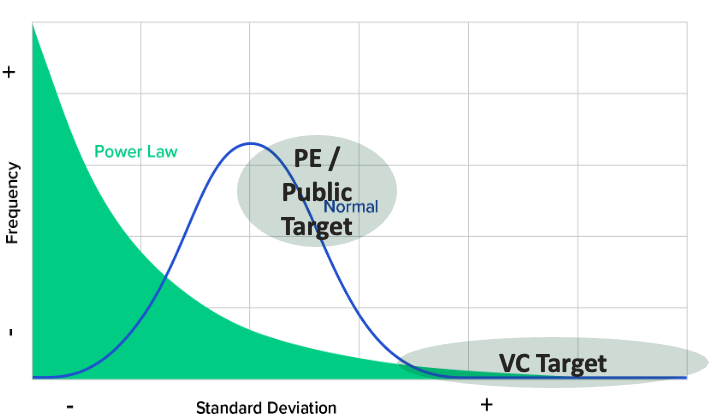

The distinction between the Power Law and normal distributions explains varying investment strategies for different classes of investors. Private equity and public market investors have normally distributed return profiles. They focus on producing incrementally better returns (alpha) while holding the variance of returns (beta) constant. Early-stage venture capital returns adhere to the Power Law, which prompts entrepreneurs and venture investors to accept higher risk while pursuing outlier outcomes along skewed right, fat, long tails of distributions. Figure 3 illustrates the different strategies pursued by venture funds compared with traditional investors.

Figure 3: Pursuing Outlier Venture Outcomes in Winner-Take-Most Markets

Ambitious entrepreneurs and their investors focus on leadership in winner-take-most markets knowing that market leaders realize disproportionate returns relative to competing firms. Most founders earn less as entrepreneurs than they would as employees in larger firms, but they launch startups anyway in the hope of achieving an outsized outcome. Early-stage venture investors endure high loss rates while relying on a few winners to deliver superior fund performance. The biggest cardinal sin of investing is passing on a fund maker as decisions on these rare opportunities can make or break funds.

The challenge with this Power Law investment strategy is that people systematically misperceive low-likelihood events. Rare events are not treated in proportion to their actual probabilities – they are often overweighted, ignored or misused depending on the context. People overweigh vivid rare events and ignore less visible ones. They overpay for insurance and lottery tickets but ignore less visible rare events such as pandemics and overact when they arise.

What appear to be minor misperceptions in an investment model produce huge swings in expected returns with Power Law return distributions. Is the upside opportunity $1, $10 or $100 billion? They are all unicorns, so why quibble? Interestingly, early-stage investors often cap upside return expectations at much lower levels since loss rates are high and very few startups produce outcomes over $200 million. Is the likelihood of achieving a winner scenario 1%, 2% or 5%? Parsing between a 1% and 2% outcome seems miniscule and prone to miscalculation, but that 1% variance in likelihood may double the potential investment return. (Disproportionate benefits for marginal improvements are widely applicable. One of my first venture investments was in price optimization software for supermarkets. By increasing selected prices on goods by 5% without changing consumer overall price perceptions, the startup could double supermarket profitability. Unsurprisingly, the startup was quickly acquired).

With such dramatic swings based on minor variations in expectations, no wonder investors are prone to flights of fancy and fits of depression. As the Gartner Hype Cycle demonstrates, markets predictably fail as investors overcorrect when adjusting their expectations. This creates arbitrage opportunities for those who appreciate and can exploit these dynamics. Following are five consistent patterns I have observed over the past four decades along with strategies savvy entrepreneurs and investors can use to exploit these arbitrage opportunities.

- Venture gains are uncapped but have a fixed floor. Early-stage equity investors risk capital invested (a 1x risk of loss) but could realize a 10x or, rarely, a 100x or 1000x return. With this return profile, investors should focus on the upside opportunity. But behavioral economics show that people, including venture investors, are loss averse. This explains early funding travails of future unicorn IPOs as the most disruptive ideas also appear to be the riskiest at the outset. Given systemic loss aversion, founders fare better, at least initially, by demonstrating an ability to manage downside risk than optimize for upside opportunity.

- Private equity investors are loss averse as their limited partners expect predictable 2-3x returns with low loss rates. They are normal curve investors who seek to avoid tail risk. When bull markets dull risk aversion tendencies, private equity investors nonetheless move into earlier stage ventures. Founders should avoid accepting private equity funding prematurely as loss aversion dictates conservative strategies that limit upside opportunity. Nonetheless, private equity is appropriate for mezzanine financing that bridges a startup to IPO as they understand public markets better than venture investors and can improve the odds of successful public listings.

- Growth-stage venture funds invest in a broad range from Series B to pre-IPO rounds. Growth-stage investors have varying investment strategies as their return profiles follow the Power Law in early rounds and the normal curve in later rounds. Founders should understand the investment mindset of prospective growth stage investors to ensure they align with the needs of their company. In hot markets, growth-stage investors often misperceive risk and assume early-stage risk while paying valuations with expected returns akin to a late-stage investor. Founders should eat when served and raise larger growth stage funding rounds with modest dilution when markets permit but manage burn rates and retain dry powder to extend the runway or pursue opportunities that emerge if or when markets correct.

- Almost all emerging technologies go through the Trough of Disillusionment in the Gartner Hype Cycle. Though many companies fail during these downturns, technologies listed in the Trough of Disillusionment have a higher success rate than those at the Peak of Inflated Expectations. Companies that survive the downturn ultimately thrive as they emerge stronger with less competition. Sadly, most founders defer hard decisions during downturns and make painful cuts too late. Downturns negatively impact startups broadly forcing investors to choose which of the few they can support. Yet our experience corroborates that some of the best returns for growth-stage investors derive from support of resilient founders during downturns reinforcing the view that investors should be greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy.

- Lenders have left skewed return profiles as their upside is limited to accrued interest while the full principal of the loan is at risk. Lenders lure startups with inexpensive loans when business is booming. But risk averse lenders often impose draconian terms that become existential threats during downturns. When lenders require equity investors to reinvest to extend the loan, highly dilutive down rounds follow. As a result, the effective expected cost of debt for venture-backed startups is much higher than it initially appears, so founders and investors should be wary of siren songs of lenders and limit exposure to seemingly inexpensive loans offered during bull markets.

I hope that the above considerations underscore the importance of understanding the nature of underlying markets. The distinction between Power Law and normal distributions is just one manifestation of market structure implications for entrepreneurs and investors, and the above examples are just a shortlist of the financial implications of Power Law distributions.

Think big and best wishes on your most excellent venture!

Related concepts

The Power Law prevails in winner-take-most markets. These include industries in which network effects and economies of scale require a large critical mass to compete. The Power Law applies to growth- and early-stage venture for different reasons: growth-stage venture returns involve high critical mass requirements and early-stage venture returns reflect winner-take-most markets in which they invest.

The Power Law, like the flywheel effect, benefits from virtuous cycles. Early success compounds future success through positive branding and reputation, proprietary knowledge in markets with asymmetric information, and network effects that offer preferred access to deals, talent and partners. Outsiders risk the domino effect of vicious circles through adverse selection. These factors compound the Three Cardinal Sins of Investing as missing rare fund makers impacts access to future winners.

The Power Law augments the importance of improved decision making. Good decision hygiene includes understanding behavioral economics and controlling for many systematic biases such as loss aversion, overconfidence and the misperception of low probability events. The consensus-contrarian matrix reminds us to apply second order thinking, which helps control for potential traps involving groupthink. A trusted wingman or inverter, who brings expert insight along with an outsider’s perspective, can also mitigate the risk of biased diligence and decision processes.

Discover more from Startup Cairns

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.